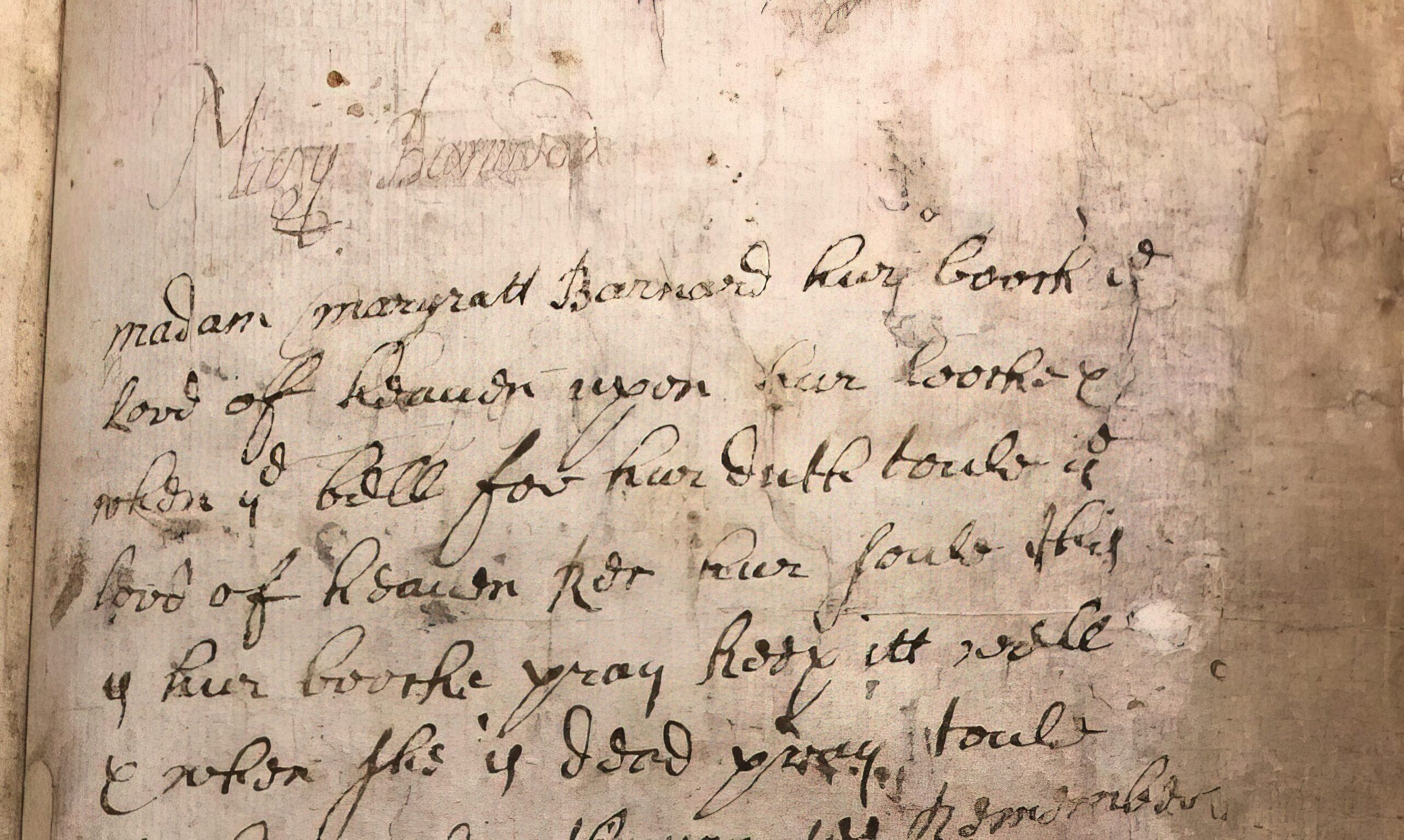

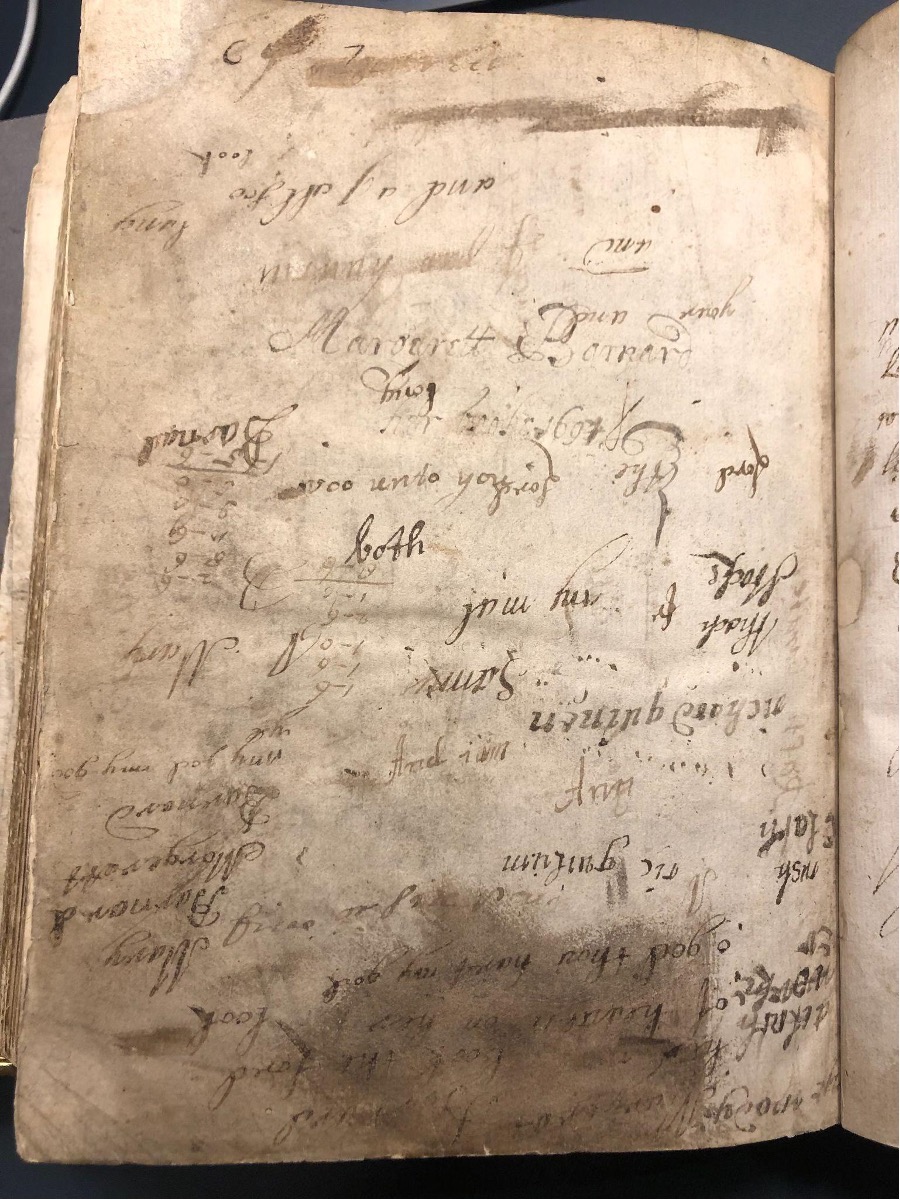

On the rear flyleaves of British Library 3052.cc.9—a copy of Tomson’s Geneva Bible—is written (in distinctive handwriting) an earnest prayer-poem by a woman named Margaret Barnard:

Note: some of the marginalia is indecipherable to me at this stage – any missing letters are noted with an ‘x’.

madam margratt Barnard her boocke and Lord of heaven upon her loocke and when the bell for hur doth toule the Lord of heaven reach hur soule this is her boocke pray keep itt wele and when she is dead pray toule the bell when this you see remember me why shud I be forgoten when I am dead and laid in Grave and all my bones are rotted h[x]th [xxxx] penetential[??] denie itt who can / margreatt Barnard is a very honest young woman as aney is in Gloucester ase that is to be found liying nor heera[f]ter ded and laid in the Ground

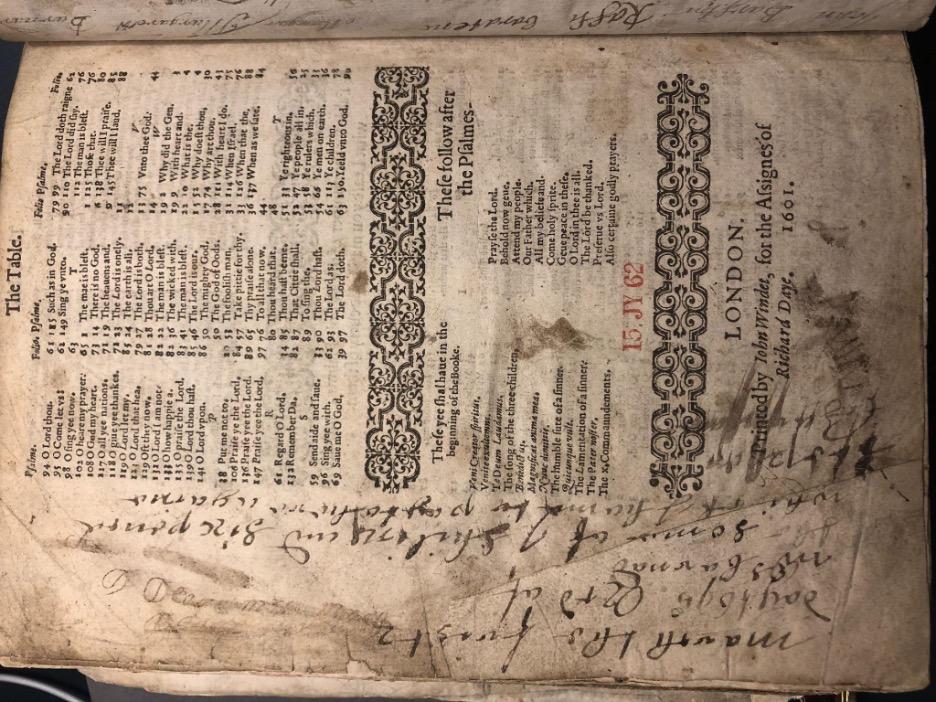

3052.cc.9 (4), rear endpaper

Not all words are easily discernible (and any insight on this would be appreciated), but the purpose of the writing is clear: Margaret is using this space in her copy of the Bible to pray for her religious salvation. Whether this is truly an impassioned plea for God’s forgiveness or simply a practice writing exercise is unclear. This writing is particularly interesting as it highlights how reading and writing can be used as a way of constructing an identity or sense of self.

Within Margaret’s prayer, she describes herself as ‘a very honest young woman as aney is in Gloucester’ both extolling her own virtues and giving herself a geographic sense of state. The simple rhyming pattern used also makes me wonder if this was a common form for this kind of prayer to take where Margaret either adapted or personalised it for her own use (though there is no way to know this for sure). Regardless, Margaret here is using the material space of the book and the physical act of writing to pray for her spiritual salvation.

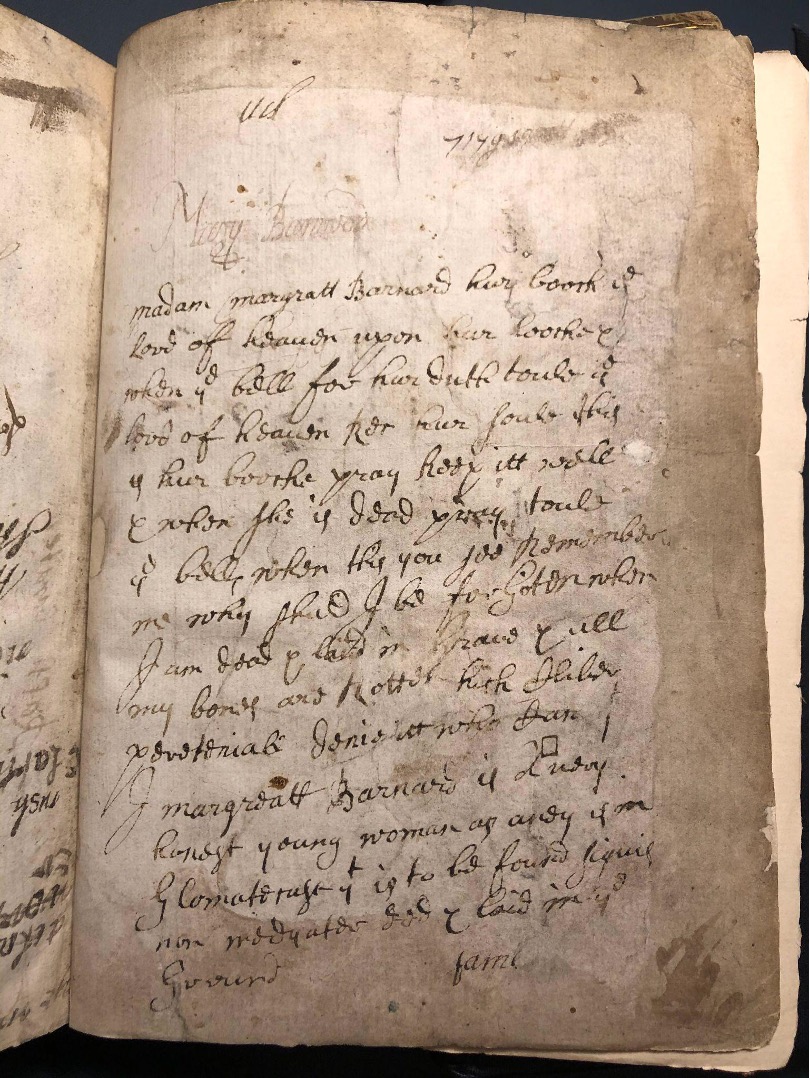

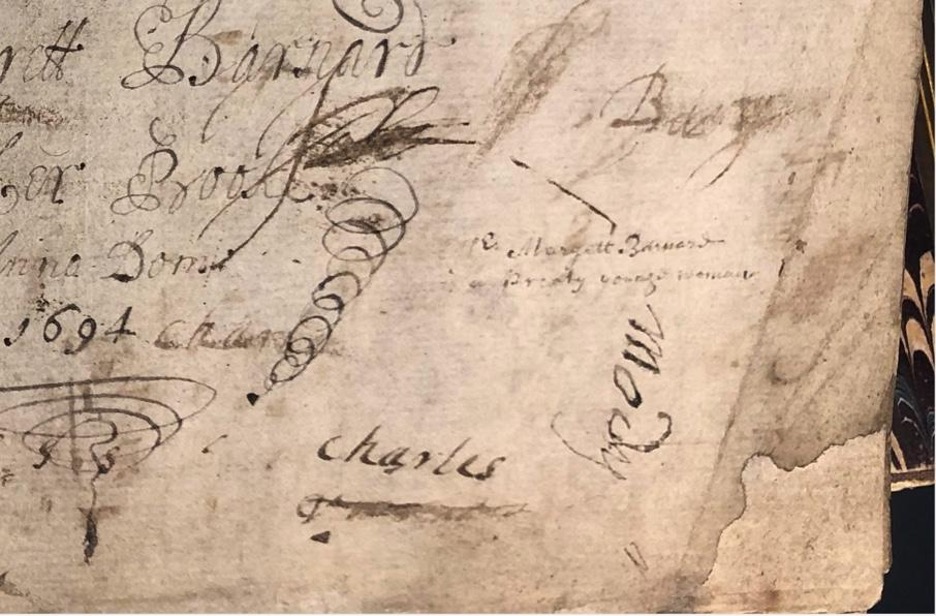

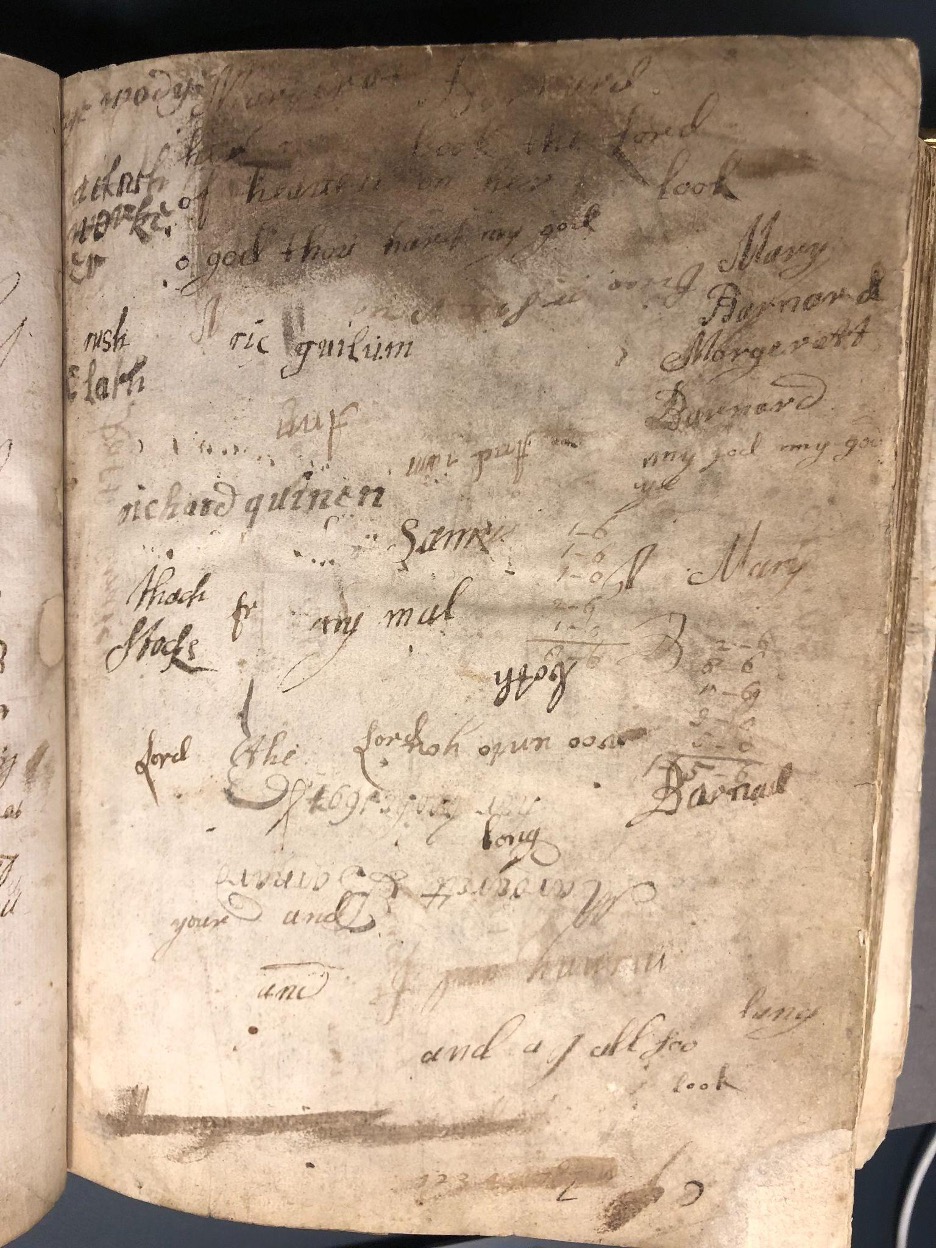

On another page in the volume is written ‘Margett Barnard a preaty younge woman’ – but in a hand which varies greatly to that of the long prayer noted above. Is this another Margaret Barnard? Is this someone else giving her a compliment? Has the original Margaret changed her handwriting?

This is a great example of how complicated marginalia attribution can be even when full names and identities are available to us. The use of the third person to refer to oneself is not unusual for Margaret, but the difference in letter formation (very small, neat letters) does give me cause to wonder as to the identity of the writer.

As other names, including that of a Mary Barnard, as well as several men’s names, are also written in this text, we know that more than one person had access to this Bible. The communality of the Bible as a text during the 17th century is demonstrated here, and so too is the sense of book ownership being interchangeable or fluid.

3052.cc.9 (4), rear flyleaf

The name Mary Barnard, in particular, appears quite frequently in this text. She never writes as substantial a piece of writing as Margaret, but nearly every time Margaret’s name is written, Mary’s also appears on the same page. ‘Mary Barnard’ is written just above Margaret’s prayer, ‘mary and’ is written above ‘Margarett Barnard her Book 1694’, and ’Deare miss Mary Barnard’ appears in faint, smudged writing above a note in Margaret’s hand that reads ‘march the first 2 day of 1696 [xxx] at m[istress] Barnad the some of 2(1?) shiling and six pence’.

3052.cc.9 (4), rear flyleaf

3052.cc.9 (4), p. 102

Mary and Margaret’s shared surname and the proximity of their signatures in this volume indicate a relationship between the two women, but whether they are sisters, a mother and daughter, cousins or something completely different is unknown. Neither Margaret nor Mary interact directly with the content of the Bible (beyond Margaret’s use of prayer as a form) but their sense of ownership over this text implies a close relationship to the content, or at the very least a sense of importance regarding this physical book for the two women.

Perhaps the essence of their shared ownership can be summed up by their own writing on the right-hand corner of a page: ‘Mary Barnard Margaret Barnard my god my god’.

3052.cc.9 (4), rear flyleaf

Hannah Upton

Hannah Upton is a PhD student in English within the School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics at Australian National University. After her BA in English, she completed her MA in Early Modern English Literature: Text and Transmission, both at King’s College London. In 2021 she was awarded the position of HDR candidate on Professor Rosalind Smith’s ARC-funded Future Fellowship Marginalia and the Early Modern Woman Writer, 1530-1660. Her doctoral thesis is titled "Early Modern Women's Marginalia and the Politics of Female Readership Practices".