In early 2021, Magdalene College Cambridge librarian Catherine Sutherland discovered a collection of books belonging to early modern philosopher Mary Astell (1666-1731), hiding in plain sight in the College’s Old Library. The collection, which initially consisted of 47 books before a further discovery of church pamphlets took the number of items to 92, constitutes an astonishing treasure-trove of information about the reading practices and textual influences of Astell, often touted as the “first English feminist” (Hill 1986). The collection held by Magdalene generously supplements existing holdings of Astell’s books in the Northamptonshire Records Office (NRO) and British Library,[1] furnishing a more accurate picture of the intellectual interests of the author of A Serious Proposal (Part I 1694, Part II 1697) and Some Reflections Upon Marriage (1700), including and beyond the “Woman Question.”

Astell’s newly discovered book collection was of immediate interest to the “Marginalia and the Early Modern Woman Writer” project because, as flagged in an initial blogpost announcing the discovery (Almeroth-Williams 2021), the books are heavily annotated by their famous owner. The most marked-up among them is René Descartes’ Les Principes de la Philosophie (1681) (Sutherland 2022), but Astell also engaged closely with her copies of Nicholas Malebranche’s works, as well as with Jean la Placette’s Réflexions chrétiennes (1707), and many other volumes besides. The humanistic scope of Astell’s reading material, which encompasses three languages (English [69 volumes], French [16], and Latin [7]) and a period of publication ranging from 1521 to 1710, is matched only by the diversity of the content of her marginalia. Astell’s marks of reading encompass inscriptions of ownership, elaborate handwritten contents pages and indices, haphazard pencil strike-lines and notate bene next to passages of interest, drawings of geometrical shapes and theorems, and more. And then, of course, there are the marginalia which demonstrate active engagement with the ideas and propositions contained within the texts, demonstrating with thrilling immediacy the evolution of Astell’s thought.

The Astell collection rewards its caller with many other noteworthy insights as to the items’ provenance, their owner’s bibliographilia, and the purposes the volumes may have served at different points of Astell’s philosophical career. For example, there are a number of bequests in the collection from Astell’s friend and neighbour Elizabeth Methuen; several of the Civil War and Interregnum-era works contain extended marginal notes left by previous female owners; and Astell’s own marginalia demonstrates a charming tendency to modulate between French to English (sometimes merging the two within a single annotation), as she presumably underwent—as Sutherland suspects (2022)—an intensive period of study in the language from the point that John Norris recommended she read Nicholas Malebranche in 1693, to the point at which the second part of A Serious Proposal was published in 1697.

Perhaps most interestingly, what the collection at Magdalene College does not evidence as much as one might expect—particularly given the nature of Astell’s engagement with books now held in the NRO, such as Richard Allestree’s popular conduct book for women The ladies calling (1673)—is a narrow or sustained feminist engagement with the ideas presented therein. This is true even of the books in Astell’s possession penned by Cartesian or Neo Cartesian authors which touch on questions of intellectual ability and physiological predisposition to error, or which intervene in the debate about mœurs. Accordingly, this blogpost will canvas a dimension of Astell’s marginalia in the Old Library collection which speaks more to her philosophical self-fashioning than to her potential centrality to marginalia studies as a thinker now recognized principally for her (selectively) radical thought about women’s right to education and choice.

- Astell’s belated objections

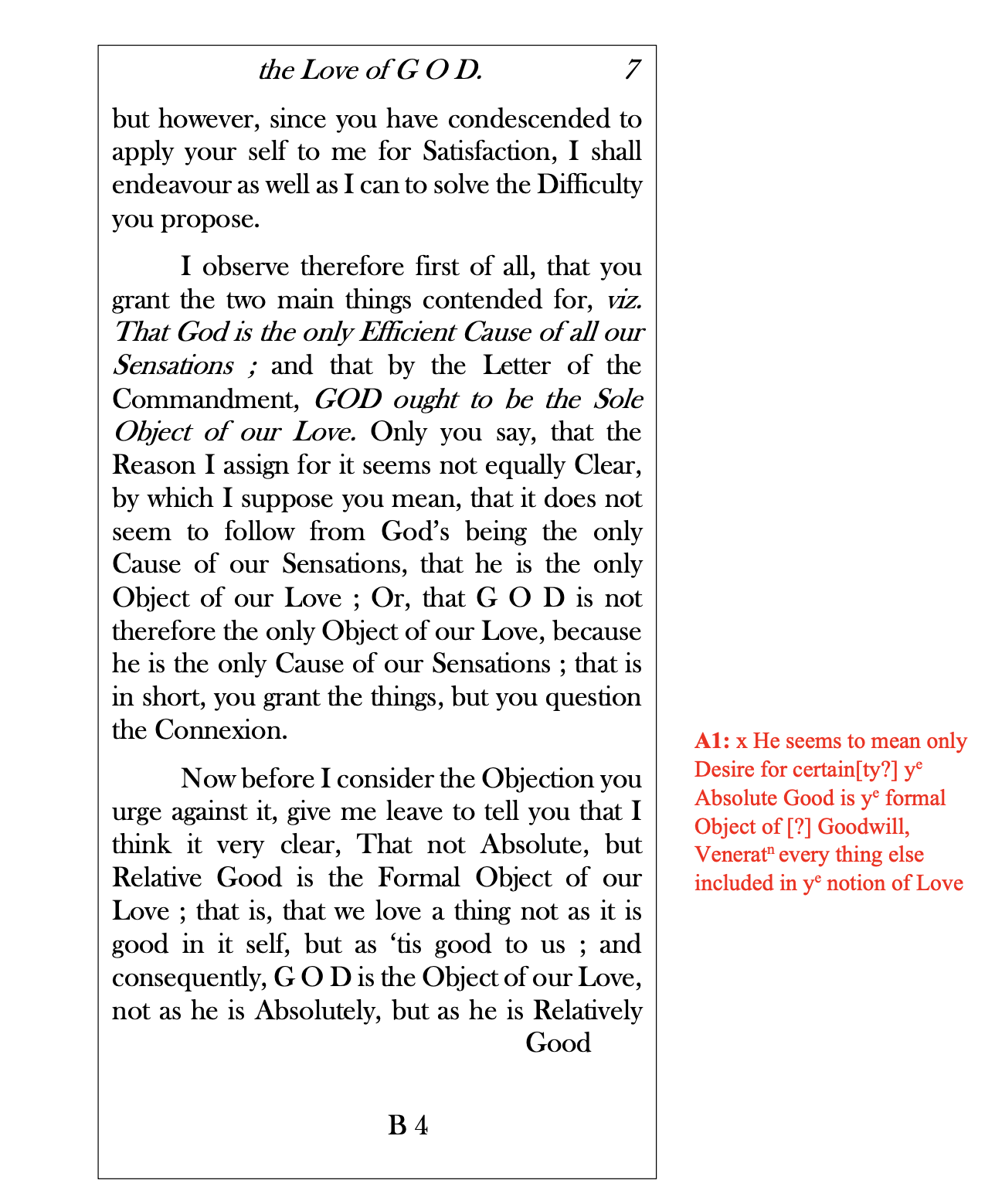

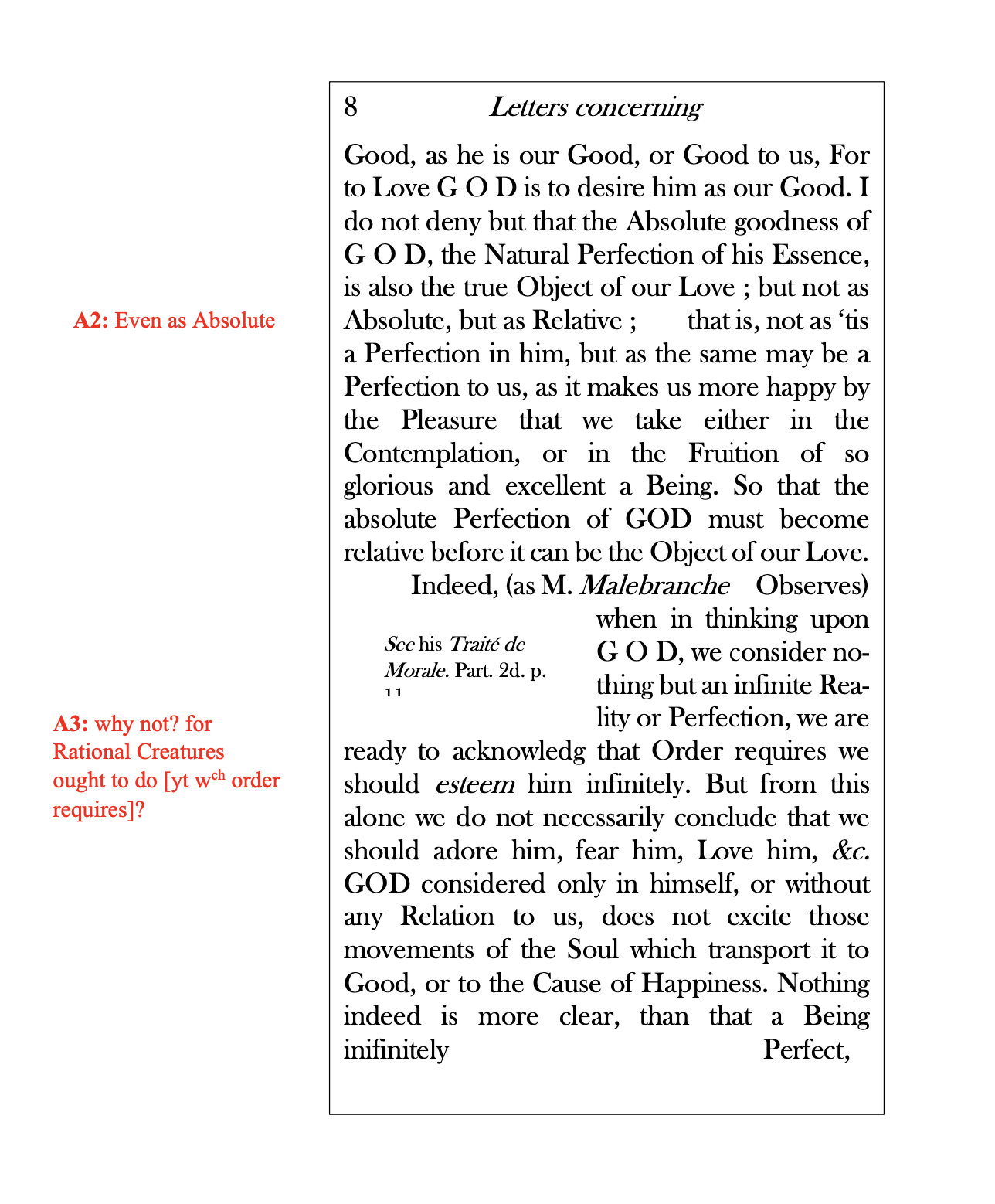

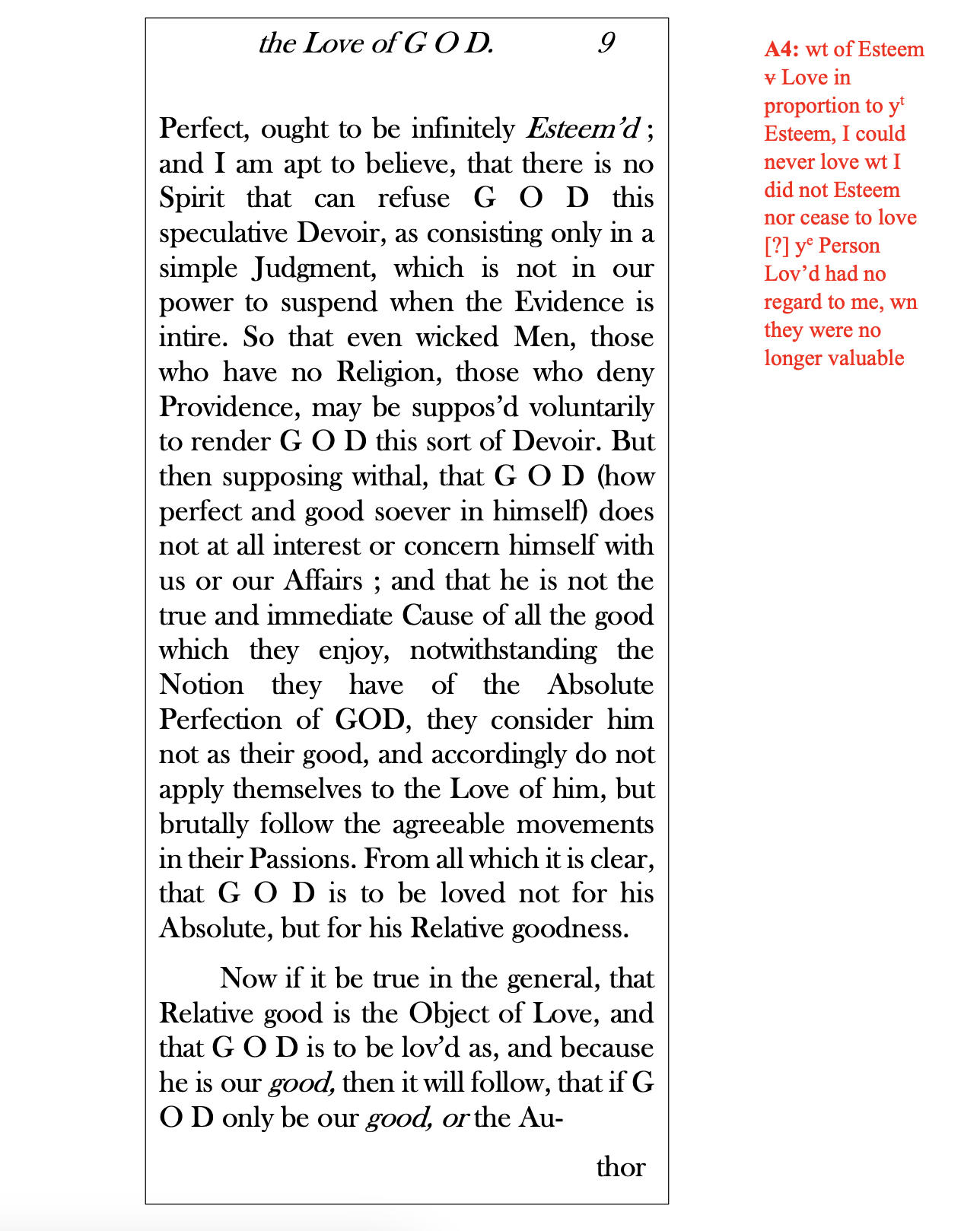

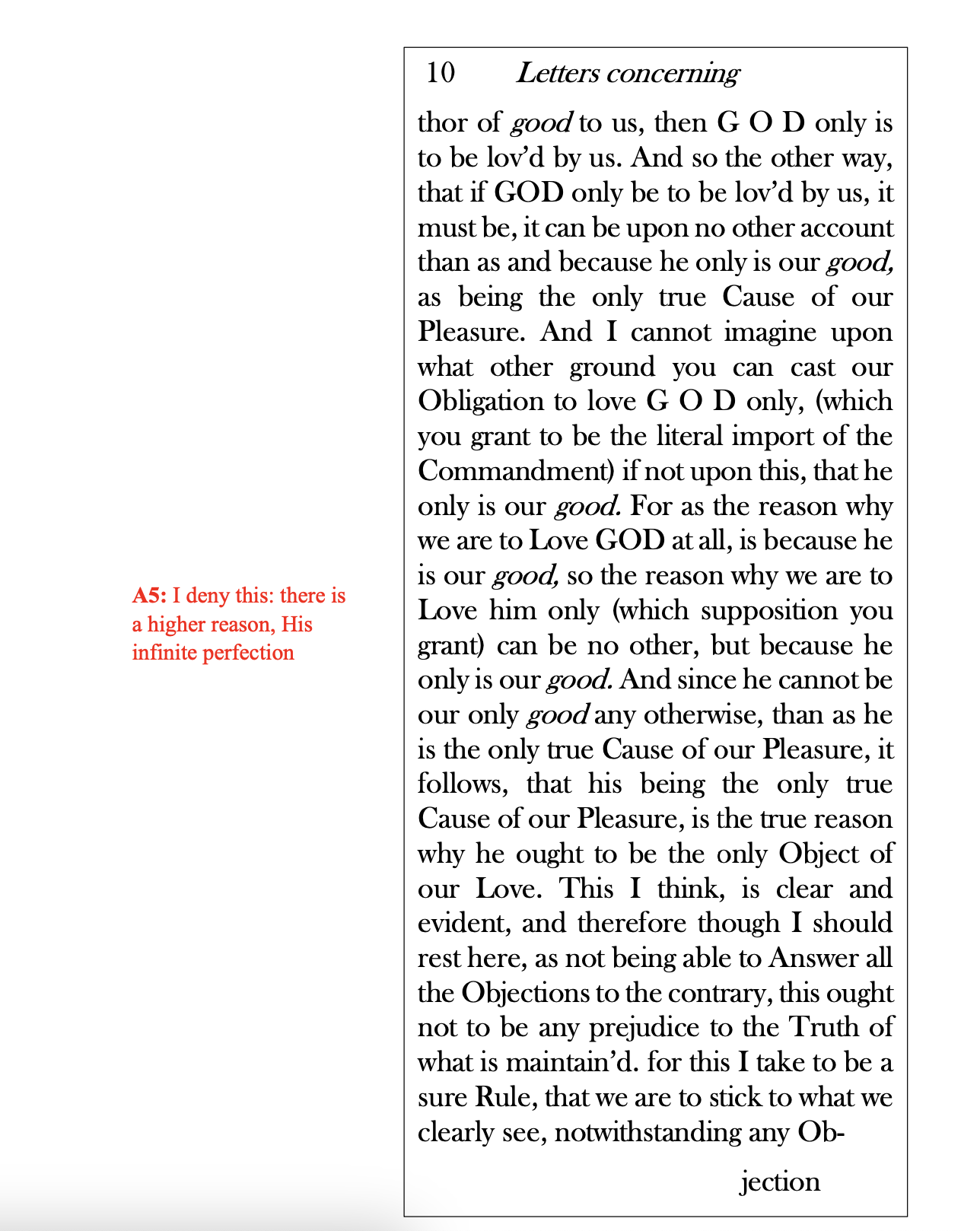

In the margins of Astell’s copy of Letters concerning the Love of God (London, 1705), the second edition of the theological correspondence between Astell and Anglican priest John Norris, we encounter a very rare instance of an early modern female writer engaging with—or rather, objecting to—a print work which immortalized her own voice and writing. Letters concerning the Love of God was first published on Norris’s initiative in 1695, two years after the correspondence was initiated by Astell and under the proviso that she would remain anonymous (she is identified on the title page to the 1705 edition simply as “the Author of the Proposal to the Ladies”). The 1705 title page features the addition of a note specifying that the work has since been “corrected by the Authors, and with some few Things added.” Astell seems to have further “corrected” the correspondence by penning several responses in the margins to Norris’s second epistle (Letter II) upon her receiving the book as part of a legacy left by Elizabeth Methuen bequest upon the latter’s death in 1723. The marginal comments, written in pencil, appear to be in Astell’s handwriting, meaning she returned to engage with her formative correspondence with Norris some 30 years later, near the end of an accomplished career which had won her both admiration and notoriety from the London literati.

As demonstrated by the pages of the Old Library’s copy of the Letters recreated below,* Astell engaged sparingly with this volume, offering only a smattering of comments across pages 7-10 of Norris’s second letter, which she likely left in a single spurt of reading activity. Yet although few, Astell’s comments pack a punch. We see a mature Astell push back firmly against Norris’s preference for the relative over the absolute good, for a finite over an infinite esteem for God, and other finer points concerning the proper way to comprehend and love Him:

Astell’s belated objections to Norris in her 1705 copy of Letters concerning the Love of God provide a fascinating window into her vantage-point as a print reader of her former correspondent’s arguments, rather than as their direct addressee and respondent. Engaging with Norris’s claims not as an interlocutor locked in the same exchange—with all the obligations to civil debate, courtesy, and female deference that such a position demanded—but as a mature reader and established writer in a room of her own, pencil freely brandished, Astell can extract herself from the context of “sociable authorship” (Barnes 2008) which gave rise to the Letters in the first place. In this respect, and in so many other as-yet-untapped ways, the marginalia left by Astell in the books that now line the shelves of Magdalene College’s Old Library promise to paint a more vivid and multivalent picture of a central figure in the history of women’s education and rights.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Catherine Sutherland and Pepys Librarian Jane Hughes for allowing me to visit the Astell collection, and for their generous assistance whilst at Magdalene College’s Old Library.

*This blogpost is not furnished with photos of the marginalia itself due to the Old Library’s photography restrictions.

[1] For the first edition of A Serious Proposal that is held in the British Library, allegedly with a handwritten inscription by Astell, see Hill, The First English Feminist, 11.

References:

Almeroth-Williams, Tom. “Ahead of Her Time: Magdalene College Cambridge Has Discovered a Treasure Trove of Women’s Intellectual History.” 8 March 2021. <https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/mary-astell-collection-magdalene-college>

Astell, Mary and John Norris. Letters concerning the love of God, between the author of The proposal to the ladies and Mr. John Norris: Wherein his late Discourse, shewing, That it ought to be intire and exclusive of all other Loves, is further Cleared and Justified. Published by J. Norris, M. A. Rector of Bemerton near Sarum. The second edition, corrected by the authors, with some few things added. London, 1705. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, <link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0119424608/ECCO?u=vuw&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=0f3fb991&pg=1>

Barnes, Diana. “Letters Concerning the Love of God (review).” Parergon, Vol. 25. No. 2 (2008): 132-133.

Hill, Bridget (editor). The First English Feminist: ‘Reflections on Marriage’ and Other Writings by Mary Astell. New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1986.

Sutherland, Catherine. “Books owned by Mary Astell in the Old Library of Magdalene College Cambridge.” The Library (forthcoming September 2023).

Emma Rayner

Emma Rayner is a PhD candidate in English at the School of Literature, Languages, and Linguistics, ANU. The title of her thesis is Gender, Civility, and Emotion in Seventeenth-Century Writing. She has published an article on poet Hester Pulter and dramatist John Webster in Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, and has an entry on poetry and emotion forthcoming in the Palgrave Encyclopedia of Early Modern Women’s Writing. She holds a BA and MA in English Literature from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and comes to ANU from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland.